Posts

Polarization is easy to achieve, but it’s hard to undo. Education is riddled with polarizing issues, both political and practical, and the issue of homework is one of the worst.

The central argument: Homework doesn’t benefit students, and you shouldn’t be giving it.

Aside from pushing buttons and for increasing retweets, search hits, and Klout scores, the homework argument doesn’t go much farther than that. Unfortunately, it’s also gotten to the point where teachers who do give homework feel ostracized in the popular education social spheres. Apparently, that means they’re bad teachers, so instead of trying to engage with an already polarized community, they hunker down and don’t bring it up.

It’s a tragedy that we can’t talk about teaching without diving into our camps.

This girl is in every blog post or slide deck about homework…including this blog post. Creative commons licensed (BY-NC) flickr photo by Cayusa: http://flickr.com/photos/cayusa/2194119780

Homework in and of itself is no more a “bad” thing than giving multiple choice tests or lecturing in class. What’s bad is when we do those things – or any thing – without thinking through what we’re doing and why we’re doing it. Rather than pushing for ideological conformity, why don’t we take time to discuss what the real issues are behind each action?

Let’s consider some valid reasons to have work done outside school hours:

Students need time to process their learning individually. This isn’t always done best in the classroom. Time to reflect, process, or otherwise chew on information alone should be done outside of school because it is more conducive to finding insight.

Practice. Don’t shoot the messenger, but skills need to be practiced. Again, corporate time in the classroom is not necessarily the best place for individual practice to take place.

Teaching time management. If we had unlimited and unscripted time during the school day, maybe I wouldn’t use this one in particular. But, when we get down to nuts and bolts, we can’t give unlimited time to accomplishing a task – and before you get all “real-world” on me, yes, it happens in places other than school.

Exploration of ideas. I would love to provide a fully immersive environment for my students, but I can’t replicate a forest in the building. Sending students out to take a walk and experience their environment requires that they do it outside of school.

We get so hung up on where this stuff happens that we miss the bigger point. Yes, I had students who took care of siblings, played sports, or worked. I did my best to limit the volume of work outside of school, but I think it’s a bigger adjustment to change what kind of work happens outside of school. Perhaps it isn’t the fact that homework exists but rather the homework we give tends to suck.

(No, not that myspace.)

I’m on my computer a lot. Having been a remote worker for 18 months and taking classes online, I needed somewhere to focus. When we bought our house, our bedroom had some recessed shelving already installed. Mishra et al. (2013) refer to architect, Christopher Alexander, and his suggestion that “the environment is best shaped by those native to that environment.” He may have been speaking about larger building projects, but reshaping our environment is a natural and expected behavior.

The entire remodeling industry is built on the fact that people want to reshape existing homes to better suit their needs. In my case, I added the desk in the thumbnail above to the bookshelves. It wasn’t a major project (before), but it was one that made the space suitable for the work (both creative and practical) that I needed to do.

I’m no stranger to home remodeling. Having some space set aside for myself was a respite from the major projects happening at the other end of the home. Again, back to Alexander: we were actively developing, changing, and shaping our environment based on the interactions we wanted to have in the space.

The article raises some interesting questions about how spaces (not just learning spaces) can be built to serve a population or a purpose, but seldom both effectively from the onset. If “architectural creativity” draws from “interactions that exist between the inhabitants of the environment,” (Mishra et al. 2013), does that mean building design has to consider multiple functions for a given space? In other words, can a room truly be built with a particular function in mind and still be effective? How much nuance comes into play with each inhabitant?

Truly effective spaces allow for flexibility in function as well as form. It may not seem like a big consideration, but having space for both old and new media on my desk allows me a greater creative range than I would normally have. Fostering both digital and analog thought allows for greater depth and refinement in “produced” work. Ideas are easier to jot down on paper and then refine out in the coding or writing process. Analogous to filming a project without a storyboard or script, writing by hand helps me find a theme to follow for the rest of the process.

Creating and publishing online has allowed for an unprecedented amount of creativity to both spill over as well as be shared. Anyone can make anything and post it online for the rest of the world to experience. New spaces often focus on providing the means to connect, as is described by Mishra et al. (2013):

The room had two large screens that could be used to project video of the participants at a distance, or to share a computer screen. There were cameras around the room, some of which could be controlled by students at a distance (using a web-based interface). The chairs in the room were unusual too: they were mobile, and equipped with iPads that could be used by participants for video conferencing.

The focus has been on giving students the means to connect rather than the means to create. Students and teachers already have devices on hand, so new spaces need to focus on accentuating the devices already present. So, rather than purchasing iPads, perhaps the space should have focused on peripherals or tools to use with whatever students walked in with. Flexibility in any space doesn’t come just from it’s use, but it what uses are afforded by supplemental tools.

Resources

Mishra, P., Cain, W., Sawaya, S., Henriksen, D., & Deep-Play Research Group. (2013). Rethinking Technology & Creativity in the 21st Century: A Room of Their Own. TechTrends, 57(4), 5-9.

Featured image creative commons licensed ( BY-NC-ND ) flickr photo shared by Jonas Tana

Shape is immensely important in science. The shape of a molecule, bone, or any other structure partially determines its function. When studying microstructures, it can be difficult for students to really grasp the complex three-dimensional structures that are proteins. I think a good analogy for this idea is the “human Tetris” phenomena. In simple terms, your function is to make it through the wall. Your shape determines how well you accomplish that task.

This is obviously an extreme example, but it’s an easy visual cue for what’s happening in our bodies all the time. In fact, you have proofreading enzymes that will break down a mis-formed protein so the constituent amino acids can be used in another functioning molecule.

Playing the Game

Proteins are complex, so we’re going to take it down a notch and use a simple reverse-engineering game to help students see the relationship between structure and function. You can expand or limit this in countless ways and in many permutations, so don’t worry too much about the particulars. One of my favorites is an old physical science task: keep an egg from breaking when dropped from a height.

Effectiveness

The function in this case is very clear – don’t let your egg break. Going about accomplishing that task really highlights the importance of a well-thought out and well-constructed container. The beauty of this game is that it is immediately accessible…there are no rules to learn and no complex interactions to stress over. Lowering the barrier for entry immediately invites students into the process of considering the structure as it carries out its function. Add in rapid prototyping and testing designs, and students are now involved in a learning loop driven by a simple goal and immediate feedback on the efficacy of their design. This is something “professional” players do regularly. Root-Berenstein (1999) quote Elmer Sperry on the prototyping idea, “I never would have realized the possibilities had I not been able thus to visualize [gyrocscopic reactions] while they were actually taking place.”

The prototyping process is also important as students transform an abstract idea to a design to a working device and reinforces the idea that in play, “things are whatever we want them to be.” Each transformation made, from a minor design improvement to a rework of their structure, is important in the learning process. Root-Berenstein also outline the transformational and play processes used by artists, and it reminded me of the mini-documentary below from the group Smiconductor as they played with and transformed data into an art installation.

Cosmos the Movie from Semiconductor on Vimeo.

I’ve also iterated on the implementation of this activity, from limiting their time to build to limiting what they can use to build. Both restrictions create a game environment and push students into higher levels of abstraction and synthesis. However, restrictions do not necessarily highlight the structure/function relationship more completely. By keeping the intrinsic load of the activity at a minimum, students can focus their energies on the structure-to-function relationship, which is the entire point of the task. Games, as with any instructional piece, can be cumbersome and unintentionally obscure the point of the work being done.

Finally, the diversity in student (or participant) solutions is amazing. Limiting materials tends to narrow the type of structure (for example, bags result in a lot of parachutes) and it’s a great way to get into discussions about why certain structures emerge more frequently than others. Again, because of the low barrier for entry and open-ended nature in finding a working solution, students can jump in and begin finding relational points between a structure and it’s function.

Interested in More?

Other building activities which could serve as structure/function comparisons include:

Resources

BBC. (2009, December 10). 2009 top fails – Hole in the wall – Series 2 episode 10 highlight – BBC one [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g9k_WOjBOFc

Jarman, R., & Gerhardt, J. (2014). Cosmos [Video file]. Retrieved from http://vimeo.com/109563495.

Root-Bernstein, R. S., & Root-Bernstein, M. M. (1999). Sparks of genius: The thirteen thinking tools of the world’s most creative people. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

The first major break of the holidays is upon us, and I’m in the mood to do some giveaways. Over the last 18 months, I’ve contributed (along with the likes of Steve Kelly, Kristin Daniels, Crystal Kirch, and more) to some fantastic books and I’ve got some extra copies that need to be read.

For this round, I’m giving away a physical copy of Flipped Learning – Gateway to Student Engagement (2014) by Jon Bergmann and Aaron Sams (pictured above).

If you’re interested, please share this post and then leave a comment below. I’ll use the random number generator to pick a winner Monday evening at 9:00 PM EST. You’ll have a day to contact me through my website’s form to claim your prize.

Be sure to add this site to your RSS feed reader for future updates and other book giveaways over the next few weeks!

Featured image creative commons licensed ( BY ) flickr photo shared by Wonderlane

I apologize for the click-baity title, but I think it helps get to the root of some emerging issues in the tech and education landscapes. I’ve got four problems briefly outlined with proposed solutions beneath. As always, comments are welcome.

Problem 1 – Closed Content

Schools nationwide are filtering content beyond a reasonable amount. I understand COPPA and FERPA and that they are extremely important. What I don’t understand is how wide a net schools are casting in their use policies with students while citing FERPA and COPPA across the board. This is not a time for blanket statements and policies. Yes, it takes more work to manage a wider range of software and web filtering, but the benefits a more open web brings students are enormous.

What you can do – Keep track of which websites and services you want to use, but can’t. Explain why they’re important in the learning process for your students and justify why they should be opened. Look for positive examples and emulate their methods in order to build a substantial case for change. Finally, volunteer to help review those requests to build a sustainable system.

Problem 2 – Isolated Devices

Hours and hours are spent choosing the perfect device to use with students. Unfortunately, it’s a lost cause – there is no single device which will make you happy at all levels. Doubly unfortunate is the fact that work done on an iPad will probably be locked into being viewed on an iPad (unless you’re publishing to the web, but even that is degrading. Also, see Problem 1.) because it is in the best interest of Apple, Google, Microsoft, and the other guy to lock you in.

Choosing a device for students should be based on what you want them to do, but understand there are compromises.

What you can do – Don’t worry so much about what students are using to create and spend more time on what they’re doing. Device purchases aside, avoid dictating specifics and you’ll see students be far more creative and open with their work that they normally would.

Problem 3 – Fanboyism

iOS or Android; Mac, PC, or Chrome – walk into an education conference and pick a fight with anyone there about which is best for students and watch sparks fly. All of this is really based on opinion fueled by “what we’ve always done.” It’s fun to poke fun at the other guy, but I’m worried that it alienates people who feel like they’re in the minority.

What you can do – It’s hard, but avoid making snide remarks about platforms that are better or worse than others. Really, you can do equitable work on any platform now, so it doesn’t matter at all which one you actually go with. Know what your goals are and make a decision that fits those goals.

Problem 4 – Identity Loss

I’ve written about this before, and I’ve brought it up on more than one occasion in conversation, but if the product is free to use, there is some hidden catch that we need to be aware of. “Going Google” has implications for us and our students that need to be weighed. Remember, you are an asset as a user of a free service – not necessarily a “valued customer.”

What can you do – Know what the costs of creating an account are. I know it’s really difficult to imagine life without Google (I still have a Google account…it’s okay…) but know what you’re putting out there. This is especially true when you ask students to create accounts online – please read the Terms of Service and Privacy Policy before pressing “I Agree.”

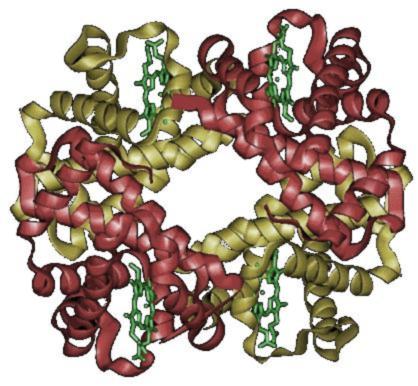

Proteins are some of the most varied, complex, and mind-bending models studied in biology. Built from our genetic code, proteins have multiple levels of organization which can be modeled independently and corporately to learn about their functions based on their structures. Because of this complexity, proteins offer great fodder for the biology classroom and helps tie molecular genetics (DNA, RNA) into the bigger picture of our bodies as a corporate unit.

creative commons licensed ( BY-NC ) flickr photo shared by alumroot

Starting small

Protein is the direct result of your genetic sequence. The building blocks (amino acids) are coded in the strand and your body uses that template to build everything. A common activity is to have student decode the template and come up with a simple amino acid sequence – this is the primary structure. The sequence of acids themselves will determine the rest of the protein’s properties.

After the acids are sequenced, they form either an alpha-helix (spiral) or a beta-sheet (flat). The structure of the helices and sheets begins to give the protein its shape in space. As they are formed, hydrogen bonds and attractions or repulsions are realized and the macrostructure begins to fold into it’s functional shape. These are the secondary and tertiary structures of the protein, and this is where students often get confused. Each time a fold is made, considerations have to be taken for adjacent functional groups and their influence on every other part of the model.

Finally, a protein’s quaternary structure comes from its interaction with other protein subcomponents. Because these molecules are so large and complex, they often form in constituent pieces which then fit together into the functional macromolecule. Your blood, for example, is a protein called hemoglobin, and it’s actually four protein subunits working in conjunction with one another.

Working with Students

A great way to have students think through the folding and conjoining aspects of protein formation is to use something like this origami-based activity where students fold a subunit in part one, and then join those units together to form a working structure in part two. They have to think through how the structure of one subunit contributes to the function of the macrostructure once it is completed. They also quickly learn that if proteins are not shaped properly, they will not function correctly.

Pedagogical Implications

Modeling in science is incredibly important. It’s hard to remember that everything we “know” about tiny structures like atoms and proteins comes from many, many years of environmental observation. We can’t actually see how a protein is folded, but we can make models based on how they interact with the environment. Students don’t realize this, and it’s important to point that out.

Everything in science is based on observation, yet we expect students to learn about structures and their functions, yet they can’t be seen. We have to teach them that first, observation is more than seeing something, and second, that models can help us make those observations. Show a student a physical model of a protein or a bone and ask them to describe what they see and feel and let the science happen. Giving them the experience of trying to fold a protein will help internalize the complexity of our bodies and what a marvel they are.

Too often, biology is complicated pictures, graphs, and data sets. It isn’t made real for students, and building models of blood cells from paper is one way to do that. Making the abstract concrete through modeling and analyzing the building blocks helps students see biology as something to be experienced rather than memorized is a big task, but it’s an important one.

Resources

Root-Bernstein, R. & M. (1999). Sparks of genius: The 13 thinking tools of the world’s most creative people. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Turnbough, M.; Martos, M. (2012, August 16). Venom!. ASU – Ask A Biologist. Retrieved November 18, 2014 from http://askabiologist.asu.edu/venom/folding-part1

I read Randy Pausch’s The Last Lecture when I was in college. In it, Randy talks about developing Alice and how it impacted his career and his views on teaching computer science to kids. At the time, I remembered thinking, “I should download and try it out.” But, I never did.

Fast forward seven years. I’ve spent the last two weeks playing in Alice, and I have to say, given my experience with Scratch, I wasn’t feeling too optimistic.

Spoiler alert: I liked Alice much, much better. I’ll continue after the video.

I said this in the video more than once, but I loved the editor. The staging area was great to set up camera angles and think through character movements before getting into the code. It really helped with my sequencing and thinking through algorithms I wanted to implement.

As with any piece of new software, I debugged a lot. I had to get used to the language the editor used as well as get used to the differences between “moveTo” and “moveToward.” They’re subtle, but important. But, what was nice about Alice is that it didn’t seem too complicated, no matter what I played with. The procedures and their layering in the methods window were intuitive and I had a good time playing with different settings to get the effect I wanted.

Alice and Scratch are very similar…the main difference being Alice uses a 3D environment and Scratch is 2D. That being said, I think I would tend to lean toward Alice as a first-exposure program for students because of the immersive environment and the ease of editing. You can step through staging into the programming, rather than diving into the programming and thinking about staging later. I also think seeing all of the available procedures for each object in the code editor is a huge stress reducer because it saves me clicks later.

There are times where I wish I could go back, rewind what happened, and listen again. Daydreamers, you know what I’m talking about. Even though it’s not in the official pillars of Flipped Learning, a reason I hear people flipping their instruction is so kids can pause, rewind, and re-watch a portion of the instruction. It sounds powerful, and it gives a great visual of students working hard on their notes, but it may not be as helpful as it initially sounds.

What does the research say?

A 2005 study focused on how students studied using video lectures. I know the technology in 2005 was far inferior to the on-demand video content we have today, but that particular point doesn’t really matter. What I want to focus on is the fact that there are some indications that pausing and rewinding content can be disruptive to the learning process (emphasis added).

Students tried to view an entire lecture in a single session; however, some discovered that pausing was necessary. All participants who interrupted viewing reported that pausing caused a serious problem which involved returning to the break point. Students reported that even though they returned to the precise point at which they stopped, they lost the context and didn’t immediately understand what followed.

The following example illustrates this point:

“A pause in watching video is worse than a break in reading a book, because I felt that I have no place to return to. I lost context.”

This is just one example of a more poignant point I’m trying to make – don’t distill the benefits of your methods down to one idea or another. Look at your strategies holistically and be able to explain how they work together to your students’ advantage.

There were interesting counterpoints to the above example in the same article:

Navigating the video backward and forward was difficult and disadvantageous for some students, whereas others found it easy and advantageous. Some examples:

“…it wasn’t easy. You sit in front of the computer for two hours and you can’t mark [content]. Rewinding is annoying.”

“…an advantage is that you can repeat something over and over, like I sometimes do when I read a book; however, I never did it. A few times I stopped and ran the CD-ROM backward and then played it again. It was easy.”

What does this mean for me?

One research study does not a law make. However, the feedback from the students in this study is interesting. In addition to the findings about rewinding content, the authors sum the study up in an interesting way:

Our first finding is that most students tried to study from video as if it was a book; in other words, these students attempted to transfer learning strategies from one medium to another.

The point is that we have to be careful about two things:

- Be careful about how you use video with your students. There is consistent frustration with students not watching them, or watching them ineffectively. Make sure your students understand how their attention patterns for instructional videos have to change. Most of our students use video as background noise – it’s in the back of their minds. If you don’t teach them how to listen for instruction, they will struggle.

- Be careful about how you talk about video with other people. Again, think about your students – if they’re pausing and rewinding, is it because they want to hear that piece again for clarity? Or because they missed it the first time through? We need to be cognizant of what the bigger picture is with instructional videos and not continue to promote surface-level ideas with deeper implications.

Other methods for repetition

Repetition isn’t a bad thing – the methods we typically rely on for repetition aren’t so great. Here are some ideas for how to revisit ideas with your students:

Spiraling. Be explicit in revisiting previous concepts in subsequent lessons. This is easy to do in science and math, where content builds throughout the year. Look for thematic similarities in English and History. Ask students to draw parallels between what they’re currently learning and what you’ve done in the past.

Context is key! Put your students into situations where they’re forced to think back to previous work. This is similar to spiraling, but it’s more than just mentioning, “think back to when we did…” Planning is important as making contextual connections in your lessons will help students solidify their understanding.

Examples. Homework keys aren’t much fun, but various examples of how to solve a particular problem or answer a prompt can help students make connections. In fact, I started flipping by recording homework examples for my AP Chemistry students. They saw the ideas again, but in context.

Lastly, remember “getting it” isn’t the important part. Yes, we want our students to have multiple opportunities to get a concept, but that’s just step one. If they don’t understand an idea the first or second time through a video, a third or fourth time through may not help much. Don’t fall back on, “Have you watched it again?” Be sure to ask questions, see what they do understand, and then build out a plan from there.

A little history

Big, important ideas can often be overlooked because of how boring they sound to the average listener. Remember SOPA and PIPA a few years back? In addition to obscure acronyms, they were also known as HR 3261 and Senate Bill 968, respectively. Or, if you want to get really descriptive, you can go by their long titles:

“To promote prosperity, creativity, entrepreneurship, and innovation by combating the theft of U.S. property, and for other purposes.” —H.R. 3261

and

Preventing Real Online Threats to Economic Creativity and Theft of Intellectual Property Act of 2011

Snore.

The truth of the matter is that no one would have paid attention to those two bills had it not been for the Internet. Reddit was the birthing ground of the Stop SOPA/PIPA protests, eventually gaining support from the Internet giants, Google, Facebook, Netflix, and others. The free sharing of ideas and strategy over the web allowed for the global public to stand up against dangerous legislation.

It’s been nearly four years, and the integrity of the Internet is at stake again.

Net Neutrality, in its simplest terms, means that anyone can create and share content equally across the Internet. No outside agency – be it company or individual – can limit how you transmit that information from one place to another. It’s how the Internet was designed, and how it’s been run, since the beginning. This principle is what allowed the SOPA and PIPA protests to be successful. It helped kickstart the Arab Spring (remember when Egypt turned the Internet off? That didn’t go so well.) and it’s been a major outlet for on-the-ground news through social media channels.

It also allows students and independent creators to have a level playing field with major corporations. This is why Net Neutrality matters to schools.

What’s happening now?

Internet Service Providers (ISPs) like Comcast and Verizon want to end regulation on the use of the Internet. The FCC used to have rules in place which regulated how ISPs could transmit data to customers. Long story short, Verizon sued the FCC, and the Supreme Court determined the regulations were outside the scope of the FCC. Now, we’re approaching the release of new regulations which have been influenced by millions upon millions of lobbying dollars on the FCC.

The new proposed rules would allow companies to create “fast lanes” of content which would be paid for by content providers like Netflix or YouTube. What are the stipulations, you ask? Those lanes must make “economic sense” to the ISPs. In other words, we’re racing for a tiered Internet if the FCC regulations are accepted and implemented.

But, it doesn’t make sense for companies to do that, so why would they?

Actually, they’ve already done it. The Oatmeal has a great post on what Comcast did to Netflix (warning: some NSFW language) in October of 2013.

` <http://knowmore.washingtonpost.com/2014/04/25/this-hilarious-graph-of-netflix-speeds-shows-the-importance-of-net-neutrality/>`__

The Internet has become a commodity – something we expect to be available. The simplest solution to this problem is for the FCC to classify broadband Internet access as a Title II Common Carrier, just like landline telephones. Access must be equitable and affordable, regardless of what you use it for.

Why is this important to schools?

Short and sweet: do you have the resources to make sure your content – or your students’ content – can be shared equally with Netflix or YouTube? Probably not.

The Internet is a truly democratic space. Yes, there are problems with culture, but the fact of the matter is that when your student creates a website, it is on the same playing field as every other website available. As a user, you should not be required to pay more for how you use the Internet – information cannot be classified as having higher value (monetary) than any other piece of information. It’s an invented factor being applied through brute force by corporations looking to make more money by inventing an economy of information. It isn’t right and it needs to be addressed.

What can you do?

There are various non-partisan action groups which have been battling lobbying organizations across the country. Two I recommend are Freepress.net and Fight for the Future. At the very least, sign up for one of their newsletters to receive press information, petition signups, and information on how to contact your legislator, the FCC, and the White House to voice your concern.

In 2012, I had my students write letters to our state representatives in opposition to SOPA and PIPA because of the harm they would cause to the free sharing of ideas. Net Neutrality is as important – if not more important – to schools today because of the fundamental principles underlying the creation and expansion of a free and open Internet. Ideas are important, and the Internet is crucial in sharing those ideas today. We need to be talking about this and taking action in defense of idea sharing and communication, and there’s no better place to do that than in our schools.

I’ve iterated on this blog a lot over the years. I started by focusing on chemistry, and then switched over to teaching and learning in general. Layouts changed, content evolved, and it’s time for one more shift for (what I hope) is the last time.

I’ve grown a lot as a teacher. I’ve gone from being staunchly opposed or advocating for certain ideas, fighting tooth and nail over ideology and finer points of what happens in the classroom. I’ve learned that language is important, and that healthy debate can help advance practice.

I’ve also learned that fighting over minor differences in opinion can stagnate growth and entrench ideas before they’re fully realized for the sake of sticking to your guns. I’ve wrestled with the idea of having a “thing” to platform myself on and how to use that to leverage opportunities and discussions. Rather than dive down the holes of what practice is “best,” I’ve decided to step back.

I’m interested in teaching and learning. I’m interested in technology. I want to explore how technology can intersect with teaching and learning in powerful ways.

I’m going to be working to tweak the layout and usability of the new site, but I want to point out that all of the old content is still here. So, links aren’t broken and posts aren’t missing. I’m looking for ideas, debate, and growth.

If you’re a reader, thanks for reading.

I lost my job on Friday.

It sucks, but life moves on.

I’ve started applying for schools, but it isn’t really a good hiring time right now. So, in the meantime, I’m speaking and doing some freelance web design. If you are looking for someone to lead a PD day at your school, please contact me through my homepage for more information. I’d also appreciate referrals and recommendations.

I’m excited about what opportunities are ahead.

This piece of the series is aptly placed after our interviews with creative people. It’s a good reminder that everyone can be creative, not just the “elect.” Creative work isn’t because of a gene or some aptitude for doing interesting things. It comes out of hard, hard work. Writing a song was an interesting lens, because most musicians have hours and hours of music behind their hit songs. Creativity needs to be practiced.

Similar to what I wrote yesterday, it takes practice to develop creative work. “Hitting the nail on the head” is much more than a lucky swing – the idea has been identified, refined, expanded, and communicated effectively. My work day to day may not be creative in and of itself, but it can serve as a foundation for times when creativity is key. We need to consider our experiences and our task at hand and blend the two into something both meaningful and effective.

Some stale suggestions

Abstractions just aren’t there.

So, where to start?

Creative spark shouldn’t be exclusive

Is it inside of me?

Where’s my muse?

Where’s my muse?

Inspect my past,

I remember that trip we took

The tan lines etched into our skin.

Old memories,

Watching old turn new again,

recollection running wild in our minds

The only thing left to do is…

Go back and check the basic

components used to be creative

Remix, arrange, imagine

Now put the idea into action

It’s time for people to see

Creative work is not a myst’ry

It’s not a myst’ry.

It’s in you as well as me.

Go back and check the basic

components used to be creative

Remix, arrange, imagine

Now put the idea into action

It’s time for people to see

Creative work is not a myst’ry

Original: The District Sleeps Alone Tonight by The Postal Service

As a point of explanation for each stanza, you can venture onward:

_Scratched out lines

Some stale suggestions

Abstractions just aren’t there.

So, where to start?

Creative spark shouldn’t be exclusive

Is it inside of me?_

The first part of the article discusses the historical perspectives on creativity. “Creativity has often been thought of as an elusive and mystical force – emerging from bursts of insight available only to certain fortunate individuals.” The next line explores the Greco-Roman myth of the muse and her role in inspiration. Even today, there is a view that creativity is exclusive to the elect. I thought this first stanza to be appropriate to set the background for the story; the song is more than a carrier of facts from an article. I wanted it to be whole representation of the piece.

_Inspect my past,

I remember that trip we took

The tan lines etched into our skin.

Old memories,

Watching old turn new again,

recollection running wild in our minds_

A key component to creativity is our past experiences – both as “variations on a theme” and people with wide experiences “have richer concepts to build on, and hence the potential to see more knobs or possibilities than those with narrower foundations.” This is not limited to content experiences – personal experiences can help us see content or instruction in new lights. It may be fodder for new examples and explanations, or it could be inspiration for a lesson design. The point is that experiences are holistic and can influence our creativity across disciplines.

_The only thing left to do is…

Go back and check the basic

components used to be creative

Remix, arrange, imagine

Now put the idea into action

It’s time for people to see

Creative work is not a myst’ry

The Heinrickson article talks about “twisting the knobs” as one of the keys to creativity, but that comes from both an understanding of what creativity is (a remix/reimagining of information) as it ties into combinatorial thinking. “…it is clear that combinatorial thinking cannot be forced or predicted, it must develop organically, determined and constrained by the unique resources that the individual brings to the creative process.” We are bringing in our ability to remix, rearrange, and image situations within the scope of our experiences.

_It’s not a myst’ry.

It’s in you as well as me.

Creativity isn’t a magical process, it’s something that we all know how to do, but we have to focus on the basic components and apply it through our lens to begin to hone the skill. History and culture help perpetuate the general feeling that someone can or can’t be creative because of their genetic luck.

Our feet are built to be durable. Bones arranged to bear weight1, thick pads of skin, and fine motor control of each individual toe2 allow us to walk upright without a tail. As adults, we rarely think about how much we rely on our feet – at least not nearly as much (relatively) as our hands or eyes. When do you notice your feet? Probably when they begin to ache – after using them for hours at a time.

Our bodies are built so efficiently, we don’t notice important functions until they cause a problem.

I’ve written about cognitive load before, so I won’t go into detail here, but as we get better at certain skills, the less we have to devote cognitive resources to complete a task. Walking, for children, takes their full attention, to the point where if they look away from their target, they’ll lose their balance. The same is true in learning – as we learn new skills, we have to devote significant cognitive resources to the task. As we improve, our mind can allocate resources to concurrent activities. Students are able to look beyond the facts and move into the area of abstraction and exploration. As with learning to walk, we can begin to explore our surroundings without losing our foundation.

We’ve steadily grown detached from our bodies. Modern living (in America) rarely requires us to be aware of what our bodies are capable of in order to survive. According to Bassett, Wyatt, Thompson, Peters, and Hill (2010), Americans walk fewer than 5,000 steps per day – we’re not used to using our feet.

At the same time, we’ve steadily conditioned students to thinking one-dimensionally. Memorizing enough facts to pass a test has been the standard. When we ask students to stretch their thinking, we run into issues because their brains haven’t been stretched and exercised properly. Just like our feet feeling worn out (arguably) sooner than they should, our student’s minds fatigue quickly.

As educators, part of our role is to simultaneously stretch and support our students. The challenge is that students’ perceptions of those two goals is different than our own. We need to recognize the physical challenge (remember, the brain is a physical thing – it grows) as well as the emotional challenge at hand. Muscles are strengthened and toned when we destroy the fibers and allow them to repair. The way we think also goes through periods of destruction and reorganization as a part of learning.

Taking small, successive steps in learning is a way to help students overcome mental fatigue.

This is an enigmatic idea; practicing rudimentary skills is often used as an excuse to drill and kill material. It falls under the realm of “test preparation,” a get-out-of-jail-free card for teachers and systems to avoid changing the status quo. We need to recognize that base information and procedure is important, but it cannot be the focus of all instruction. As with walking, we have to focus on putting one foot in front of the other, but I’d like to be able to look around once in a while.

Resources

Bassett Jr, D. R., Wyatt, H. R., Thompson, H., Peters, J. C., & Hill, J. O. (2010). Pedometer-measured physical activity and health behaviors in United States adults. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 42(10), 1819.

Vanderbilt, T. (2012). The crisis in American walking: How we got off the pedestrian path [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.slate.com/articles/life/walking/2012/04/why_don_t_americans_walk_more_the_crisis_of_pedestrianism_.html.

Have you ever been leading a session and been faced with the statement, “That’s great, but what does it cost?” The new economics of education rely on free as the baseline of worth in the classroom, and that’s bad for ideas and growth.

I know that money is tight1. I’ve spent hundreds of my own dollars on classroom supplies, materials, lessons, and tissues…so many tissues. I’m concerned that the value of materials is rooted in what it costs rather than its instructional value, which is both good and bad for education.

We need to differentiate between the free sharing of ideas and the free sharing of products.

The two are not synonymous, yet they are often equivocated. Consider the following:

I may share an idea on Twitter, my blog, or at a conference. It could be a lesson plan, a lab activity, or something to do with students learning. I have no ownership over any part of it, other than it’s something I came up with. The idea is ephemeral…it lives and dies with the action that’s taken.

Someone reads or hears the idea and runs with it. They create a lesson plan, supplemental materials, and other products which can be shared – maybe even a curriculum or an ebook.

Are they wrong for wanting to get some return on their investment of time and energy by asking for a small fee for those materials?

Depending on who you talk to, yes.

I didn’t ask anyone, but I know that making a living off of selling content is really, really hard in today’s education economy. What bothers me the most is that people (individuals, not corporations) who sell materials rather than giving them away are really hearing, “My time as a teacher is valuable, but not what I make with that time.”

A refrain I hear is, “I give all of my materials away for free, so others should do the same.” We’re projecting our own values onto others in the community! I can’t think of a much more damaging sentiment to communicate to colleagues. I’d even go so far as to say it’s bordering unethical behavior by expecting others to work with their products in a way that suits the community rather than their own goals. You can better a community and make money at the same time.

How many entrepreneurs have been stifled because of the “free-and-only-free” expectation? How many conference sessions have been unheard (or even commandeered) because it didn’t focus on free stuff? An economy of free isn’t sustainable, and I’m worried we’re losing valuable insight and growth opportunities because of the path we’re on.

Ideas vs. products. It’s important.

- I know I’m not in the classroom right now, but I still experience this reaction when I make suggestions of resources for use in the classroom. Free isn’t always worth the hidden costs.

I’m not going to lie – I found this week’s assignment really, really difficult. More on that later.

Nearly all of the coding I’ve done has been in front-end web development. I like playing with HTML structure and seeing what I can do with CSS. Lately, I’ve been creating a blog template which added some significant PHP and jQuery. I enjoy working in text editors, the command line, and the development tools in Chrome. I like text.

Scratch is the complete opposite. Everything you do is represented with graphics. Loops are large brackets which take blocks of code, operators modify events as different shapes…I didn’t find it very intuitive, to be completely honest. I spent most of my time trying to remember which color corresponded with which shape so I could get into the correct menu. There was a lot of clicking, a lot of eye rubbing, and more than one trip away from the computer to clear my head.

The entire process of programming in Scratch is rooted in abstraction and decomposition. I know what actions I want the sprite to make, but in order to get that to happen, I need to think through each and every step leading up to the result. Once I had an idea of what steps needed to be accomplished, it was time to put them into sequence and think about how to chunk the project up.

I started with a small drawing program. It isn’t very advanced…but it took me a while to get through because I had to think through each block and what it was doing step by step.

After adding each command, I would test the program…then debug. Rinse. Wash. Repeat.

It still amazes me how much the final product changes from the initial idea. At first, I wanted the sprite to jump around the page, drawing random lines to see what could be generated by chance alone. That isn’t much fun for the user, so I moved it to a follow-the-mouse game. A concept I remember from my art classes is continuous-line drawing, where you draw without lifting the tip of the pencil. I always enjoyed that style, so I decided to put it into a little game you can play.

Now that I have some chops, I went back to the game-of-chance idea. This game is based on luck alone, and it came from the “do something surprising” prompt in the Creative Computing handbook.

This project threw a new loop at me (get it? loop?) and I really struggled with writing separate scripts for each individual sprite in the editor. I expected one main editing interface, and was really confused about where my scripts would go as I added sprites and backdrops. Again, I think this goes back to my experience with written code and managing everything in the flow of one document. (If you’re curious, this is called “object-oriented programming,” something I’m familiar with, but not nearly competent in.) So, this exercise turned into a major learning experience for me.

I found myself – again – digging through, step by step, experimenting and testing, until I found patterns that I could build off of.

It’s important to remember that Computational Thinking is all about the problem-solving process.

I was sketching diagrams, talking out loud, and looking at other examples as I figured out where I was failing. The great thing about computers is that we can rapidly implement ideas and iterate toward a working solution…they help us quickly isolate problems and work toward solutions. So, the computer is extending not only our creative capabilities, it’s helping us refine those ideas in an efficient way.

We can emulate that process in any activity, especially in the classroom.

It’s important to remember the struggle [STRIKEOUT:we feel] I felt during this exercise is how someone feels daily in my classroom. Patience, empathy, and understanding the components of working through problems are essential for me as a leader and equally essential for students to learn.

When you touch something hot, the nerves in your hand will immediately fire a signal up toward your head to make a decision about what to do about the “hot thing.” But – here’s the cool part – your nervous system is smarter than that. Your spinal cord sees that warning go past and tells your hand to pull away – no brain needed. In fact, you don’t even realize you’ve pulled away until after it’s happened because your brain hasn’t received the signal from your hand yet. Wild.

Analogy 1: Pulling Bach

Make sure your volume is up, then click the animation

Bach’s ability to layer the theme in a count-counterpoint method was unmatched. Listen closely – the right and left hand of the pianist are playing the same pattern, just at different octaves and at different times. Yet, they overlap to compliment one another. Our brain does the same thing…variations on a theme (sending and receiving signals) at every moment of the day unmatched in efficiency and power by any machine built.

Analogy 2: Coordination and Node Structure

Click to expand in a new tab.

The nervous system isn’t a straight A-to-B system. It’s a complex network of feedback loops which feed information between nodes in response to the environment. The global air traffic network is more than the sum of it’s routes…an issue at a single node anywhere in the global network will be felt downstream. The same is true for our sensory networks – a delay in our reflex arc, for example, can lead to serious damage to our tissues.

Building solid analogies requires that we step out of our own area of expertise and think as a novice.

The most difficult part of this assignment was avoiding direct comparisons – particularly those based on physical structure. I also think a good portion of building a solid analogy is thinking outside of my own understanding – approaching the idea or problem for the point of view of someone who has no experience with the topic.

In fact, it’s how I built the Bach analogy. My wife and I were discussing analogies and this assignment, and I was explaining some of the examples given in Sparks of Genius (in particular, the vibration of electrons). She suggested that I apply music to our nervous system because of the way it is built. I immediately thought of the call-and-response (counterpoint) style of music, and was able to build that into an explanation of how the reflex function works. Before speaking to Lindsey, I was limiting myself to structural comparisons…I was thinking too literally about what I already knew. I then used the same approach to draw the second analogy between our bodies and the air patterns of the world day to day. I may not be able to talk about the actual structure of nerves at this point, but everyone can relate to a delayed flight at some point. We now have a truth which bridges our experiences.

As teachers, we often rely on our content knowledge more than our context knowledge. We fall back on “explaining” rather than “exploring” because it’s safe, and frankly, it’s how many of us were trained before entering the classroom. That being said, we often analogize on the fly – we come up with examples and comparisons to help ease confusion and frustration. Consider keeping track of those and refining the ideas to become more central in your instruction and not so situational.

I’m expanding on a post I wrote a week or two ago in which I added automatic Flickr attribution to header images on the blog theme I’m working on. I wanted it to be done on all images on the blog, and I finally got the script after playing around and with some help from StackOverflow. Here’s the skinny:

I didn’t expand my original script – I want that one to run on its own because it styles the credit a little bit different than the body text. Rather than overlaying a credit, which would require some HTML restructure, I’m simply adding it below the picture because KISS is always the best policy.

Here’s a CodePen demo of the script in action.

A couple things to note about the script:

- Right now, it only adds a credited caption to Flickr photos, because, let’s be honest: they have the best API for this kind of thing. Don’t hope for anything like this on Instagram any time soon.

- It specifically looks for the Flickr URL before running the script, so your site won’t be bogged down with scripts running.

So, there it is. Take it as it is, or take it, mess with it, and share it back.

Also note I’ve got a larger project going which will get its very own post someday soon coming up.

I’m on bath duty each night. After dinner, the water runs, and Meredith gets really, really excited. The tub is full of boat, plastic chains, and foam letters which have a great feature of sticking to the wall when they’re wet. I’ve even discovered that, if thrown just right, they will stick on their own.

I don’t want to humblebrag, but I can get it to stick one out of seven attempts.

I managed to get a “G” to stick tonight and I started wondering why it stuck to the wall…is it cohesion or adhesion?

I’m still thinking through how to best explain this…which force is more prevalent? Is is one more powerful than the others?

When I taught adhesion and cohesion, never considered a problem like this…they were all straight forward because I had to assess the standard. I was afraid of confusing them. Now, I’m more afraid of what I missed because I didn’t confuse them.

How would you explain the picture? What would your students say?

Structural patterns exist all around us, especially in living systems. A common example in the biology classroom is bone structures which show evolutionary similarities between species.

My biology courses begin at the cellular level and explore the basic structures of life. Phosopholipids, for example, make up our cell membranes. Each individual molecule has the same structure and in aggregate, they serve a critical function in regulating the life of every cell in our bodies.

Patterns in the scientific sense often lend clues to the function of the system they belong to, and they can help us make insightful observations of new systems. New questions arise as patterns emerge and are analyzed in new ways. I want my students to look for similarities in observable features (particularly in biology) and use those observations to build hypotheses about new systems. The skill of pattern-finding is important in itself, but it becomes more powerful when applied in context with the content.

Patterns dictate every aspect of biology, and we are inextricably part of those patterns.

Traditionally, freshman biology curricula begina with atoms, molecules, and cells, and work their way to larger structures and systems. This is a very abstract approach which most ninth grade students are not prepared for (prerequisite science is usually a physical science of some kind). Rather than looking at structural patterns and their functions, it makes more sense to begin with patterns which affect their lives.

Consider the changing seasons: life on earth is made possible by energy from the sun. As energy availability changes, patterns in living things also change appropriately. Plants and animals move into (or out of) dormancy; part of the shift to dormancy may include structural change (ex. losing leaves) due to those functional shifts. The seasonal shifts physically affect students – they can connect the pattern to their own lives. This can be extended to the cycle of life and death, both in a macro- and micro-biome. When natural patterns are disrupted, problems emerge, and they can now be approached with a concrete frame of reference.

What does this mean?

Patterning is important in science because it can help set a frame of reference for further study. Typically, this is done by studying the microstructures which dictate systemic functions of plants and animals. While effective in some situations, may biology courses are built starting with small (cells) structures and leaving the big (plants, animals) to the end of the year. But, with exam pressure and other end-of-year stress, many of the macro-level units are touched in spirit only.

Rather than focusing on structural patterns first, focus should be given to identifying and observing patterns students are more familiar with. Exploring environmental factors which can influence an organism is more in line with them empirical science they’ve done in years prior and helps build an answer to the question, “why?”. I understand the danger in making blanket statements like this, especially because each student comes to class ready to engage in different ways.

@bennettscience Students developed in abstract thinking, micro to macro works well. More concrete thinkers need macro to micro (difficult).

—Chi Klein (@chi_molecule) October 5, 2014

So, while I would prefer to start with recognizable patterns to help forge connections to the content, it really comes down to knowing my environment and adjusting as needed. It takes a blend of ideas – giving opportunities for concrete exploration as well as abstract can help bridge the gap created when one method is used exclusively over another. As the teacher, it is my responsibility to help students make those connections, regardless of the particular content. Spiraling, scaffolding, and exploration can all be used in the process. The key is to be aware of what patterns exist congruently and work to take advantage of each.

“My work isn’t always incredibly creative, it’s just different than the way other people think about the same things.”

Vicari Vollmar

Creative work is defined by circumstance – we work creatively for our jobs but we also work in creative ways for personal fulfillment. Each requires a different mindset and each results in its own reward.

For instance, if creativity is defined by a work’s “novelty, effectiveness, and wholeness,” (Mishra, P., Henriksen, D., & the Deep-Play Research Group, 2013) in a work situation, effectiveness comes first. “Function supersedes form,” as Vicari put it. Her creative work (design) needs to communicate an idea first and foremost. Conversely, Kaitlin said the best part of working in her kitchen is “getting it right.” Hitting the flavors, texture, and appearance of a baking project (wholeness) is the goal.

We also discussed the nature of creativity…in other words, is creativity in the product1 or the process? Both Kaitlin and Vicari believe that creativity resides in each individual.

Here’s an analogy: You and I are given a task to complete. We go our separate ways and do the work; we experience and respond to the prompt in unique ways, which leads us down unique paths for a product. Regardless of the final medium, we have gone through our own creative process. Additionally, the product does not need to shared with anyone else in order to have been creative. Kaitlin often bakes because she wants to bake. Vicari writes because she wants to write.

Creativity is not rooted in the product, but in the product’s creation.

So often, our interpretation of the value of our work comes from others. I may take a photo, but compared to other people’s, it isn’t very “creative.” Perhaps it isn’t as novel, but it may be more effective at communicating an idea. Novelty is often over-emphasized with effectiveness and wholeness falling aside. Perhaps this is because the novel work is celebrated by culture; it’s what is passed through email and discussed at lunch. It causes discussion, inflating its importance in the creative process.

External affirmation is linked with creativity, I think, because of our culture celebrating musicians, artists, athletes, and other public figures. I don’t think this is wrong, but it often dilutes the innate value in thinking and acting creatively because of the limits we impose on ourselves. Creativity and talent are often blended, and it leads to confusion over what true “creativity” looks like.

Vicari and Kaitlin helped expose the value of the process we follow to create. Being cognizant of the purpose of the creative task is going to play a big role for me. I often bog myself down with novelty and not enough effectiveness or wholeness. Thinking with purpose and the big picture in mind is the first step to improvement, and it’s one I’m learning over again each day.

Special Thanks

Many thanks to Kaitlin Flannery and Vicari Vollmar for answering my half-baked, very ambiguous questions this week. You can read about Kaitlin’s baking on her blog, Whisk Kid. Vicari has just started her own blog, So Vicarious.

Notes and Resources

Mishra, P., Henriksen, D., & the Deep-Play Research Group (2013). A NEW approach to defining and measuring creativity. Tech Trends (57) 5, p. 5-13.