Posts

Since early this year, the WHO has been calling for international aid in response to a burgeoning crisis in west Africa. There had been a confirmed death and further infections due to Ebola virus. Initially, it’s mortality rate was above 65% for infected individuals. Fast forward six months and the death toll has topped 3,000 with five countries officially recognizing infected individuals.

It hasn’t been in the news much because the media typically covers “disaster moments.” NPR’s Planet Money podcast took an insightful look at why it is just coming to American’s attention. I decided to grab some readily available data from the CDC, the WHO, and other international relief agencies to put some of these numbers in perspective.

History

Ebola virus data is easy to track down because it was only identified in 1976 in the Philippines. Since then, every outbreak has been documented by major health organizations. Most of the cases since 1976 have occurred in central Africa.

Confirmed Ebola virus deaths in Africa, 1976 – 2012.

In the past, these infections have been isolated to remote regions in the bush country (Ebola is contracted from contaminated bush game meat), so transmission was limited. The current outbreak region is centralized in heavily-populated urban areas.

Confrmed Ebola virus deaths in Africa, 2014.

Higher population density with low-quality health care facilities translates to a higher rate of infection. How much higher?

Historical Perspective

There have been Ebola virus outbreaks every few years since it was identified in the late 1970’s. Like I mentioned earlier, these cases are well-documented by health organizations globally. This year’s outbreak is nearly three times as large as all other outbreaks…combined.

Documented Ebola virus deaths 1976 – 2012 to the present outbreak.

The infection rate has also skyrocketed due to the urban spread of this particular outbreak.

Rate of Ebola virus infection, 1994 – present

Hope

There is a sliver of good news in this last picture: the mortality rate is slowly decreasing. Typically, the mortality rate for Ebola virus infection hovers around 50%. The current outbreak mortality rate, overall, is roughly 30%. However, individual nations have varying rates (Liberia has a 54% mortality rate currently). As international aid and global awareness increases, the transmission of the disease will eventually slow. However, if international response is not increased significantly in the coming weeks, the infection rate will continue to grow exponentially, and the virus will continue to jump borders.

All of the aggregate data can be seen here.

The essence of abstraction consists in singling out one feature, which, in contrast to other properties, is considered to be particularly important.

Sparks of Genius, p. 72

Looking past the obvious is hard to do, especially when you’re up against a deadline. Our quick-to-consume culture has conditioned us to see the world in snippets…short bursts of stimuli. It’s marketed as “consumable” or “digestible,” but it’s a cheapened experience.

Root-Berenstein (2013) characterizes Werner Heisenberg, Picasso, and others, finding the root of abstraction in “finding the minimal visual stimulus that can be put on paper or canvas and still evoke recognition.” Consistently, the simple concept defined through an abstraction can be applied to the bigger picture.

This is hard because it takes time. There is significant effort in abstracting seemingly simple ideas, objects, or actions. With photography, it is difficult to capture an abstract idea because the camera lens gathers so much information with the flick of a mirror.

Identifying main themes in any abstraction will help with breaking down complex ideas. What patterns exist? How can those patterns be grouped together? What other patterns emerge as you break things down? Often times, in the process of identifying a theme or themes, you can combine ideas into simpler, more generalized themes. Repetition is key in this process because you can look for common threads. This also means that our first attempt can usually be thrown away. Abstraction, in its truest form, is the result of a process, not creation through obscurity.

Resources

Root-Bernstein, R., & Root-Bernstein, .M. (1999). Abstracting. In Sparks of Genius. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

It’s important to use attribution online. When you pull a picture, make sure you tell other people where it’s from. Some sites make it easy for you to do that, others…not so much. Flickr used to be great at making attribution easy, but their latest redesigns have made it harder to accomplish. Alan Levine has a great CC attribution gizmo which makes it super easy to both give credit to and share a photo from Flickr. I use it all. the. time.

WordPress is great – I use it for this blog and my class websites. I even ran my own multi-site for my students one year using WordPress because my administrators at the time didn’t want blogs out in the wild. So, I did it for them. Anyways, WordPress doesn’t have the best method for featured images. You can’t use an image source URL to share it…you need to download the image and then reupload it to your site. It’s really easy to “forget” to post attribution.

I’ve been playing with another open source CMS called Anchor. It’s very bare bones right now, but it’s super flexible in terms of what you can do. Because I didn’t have enough going on (read sarcasm there…) I decided I wanted to create my own custom theme for an Anchor blog. I’ve got a demo site up right now (which will be changing soon…updates are coming!) and one thing I had to include was featured images from a URL.

The next step was to get attribution in there…not just a link back, but an actual box of text with the post title at the very least. Flickr has a powerful set of APIs which can be used to get all sorts of data which you can then bend to your will.

For those too wary for code, here’s the tl;dr – this new blog theme in Anchor will automagically attribute featured images you include. All Flickr images are coming soon.

The problem – In order to use the Flickr API, you need – at the very least – a photo ID. Because I’m attaching the photo using CSS, I have the source URL of the image. Here’s an example:

I needed a way to get that snippet of the URL into the API call. Unfortunately, there is no one step that can do this. So, I went and gave myself a crash course in regular expression to get that information into a usable form.

Of course, there’s another issue in my way. The CSS holding the URL for the image has characters in the syntax which I can’t use:

The solution: use another regular expression snippet to pull it out.

If you’re following along, if you put console.log(bg) into your editor, it’ll return a clean URL.

Now that we have the URL, it’s time to extract the photo ID only because that can be used in the Flickr API to build the attribution URL.

Like I said earlier, I gave myself a very crash course in regular expression, so this very…very ugly expression1 strips everything except for the photo ID and stores it in a variable for later.

OK, we got the URL, then we got the photo ID. Now, it’s time to build the URL to request information from Flickr about this picture.

This is the URL that we use in the final step of the process to get information from Flickr and then build one more URL, which becomes the attribution link.

This last asks for JSON information from Flickr and then we use jQuery to apply it to a div created in the HTML to hold the information. Flickr URLs all have the same structure, so building a link back to the owner’s page is easy. I just pulled out their user ID number and reattached the photo ID we grabbed earlier.

If you want to play with it yourself – changing the photo and everything – you can do that in this CodePen demo I set up during testing.

This is a lot of work to automate the link backwards, but hopefully, it’ll make it easier to add attribution back with every picture, not just ones you remember to grab information for. Again, this only work with Flickr at the moment, and only for featured images at that. I’m planning on expanding this to any image in a post pulled from Flickr as soon as I have time. Or, you could do it. Just share it back when you do.

- no one said code had to be pretty to work

Sometimes the simple challenge to think concretely about abstract concepts can be effective.

Sparks of Genius, p. 64

Perception is how our mind interprets data. Those interpretations are influenced by our surroundings, experiences, and biases. Root-Berenstein (1999, p.43) point out that “objective observation is not possible” because of the own influence our mind has on our senses and how they interpret information from observations.

I started this exercise by thinking about how we make observations in the biology classroom. Much of high school biology is focused on micro-scale systems – cells, molecules, etc. Observation of these systems often take specialized equipment which allows us to diagram, document, and otherwise describe what we see. I had a hard time reimagining how we experience those systems in meaningful ways, so I shifted my thoughts to macro-scale observations which relate to structure and function.

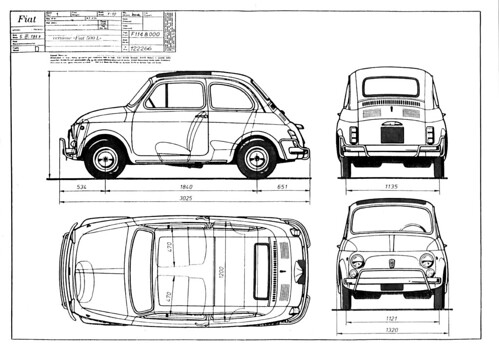

A car’s structure helps it function effectively as a mode of transportation. We can look at diagrams and plans for different cars’ structures and what their likely function is (eg. comparing a minivan to a drag racer). But a car is so much more than functional. A car can provoke emotional reactions – gut feelings about it’s carness.

Perceiving is much more than just observation. The smell, feel, and sounds in addition to visual information help us form an entire picture. The car example I described is something we can all relate to. The feeling of acceleration, the smell of the gasoline…each adds to how we experience a car. The same can be true in the classroom.

Biology is a collision of abstract and concrete. If our metabolic processes were to shut down – an abstract idea to students – we would die in very concrete terms. Unfortunately, in many classrooms – mine included – the reality of concrete biology is lost due to the hyper-focus on abstract ideas. Students only see life as described through a textbook. Michael Doyle is a biology teacher in New Jersey who often writes, “stuff is stuff…nothing can change that.” Even though that stuff is very small, it’s still there, and our students need to experience it in new ways.

Diagrams and models are important, but there’s a lot more to things that what we see at first glance.

We cannot focus our attention unless we know what to look at and how to look at it.

Sparks of Genius, p. 42

There's a concept in biology which says that structure and function are inextricably linked. In fact, you can boil down any part of the study of life into looking at the structures of plants, animals, insects, cells…even molecules – and analyzing what they do in their environment. For instance, the structure of DNA – repeating nucleotides in specific sequences – makes it uniquely adept at storing information. Structure and function.

Much of biology is done with our eyes. We have to look at a structure or observe a behavior in order to find the links. Analytical tools and measurements are a key components of studying living systems. Smell and hearing also play a major role. If you talk to an ornithologist, most of the identification they do in the field is based on the bird's song because seeing them through dense foliage is difficult.

Rather than discussing biology, let's use a more accessible model: a car.

Cars are described all the time with terms like “horsepower, “average MPG,” and “torque.” You can look up specs, schematics, and plans online for the newest models. Top Gear, a top-rated British television series specializes in reviewing luxury and performance cars each week (among other things).

Let's get visceral.

Perception is more than seeing what's in front of you.

Loops

When I got into coding, loops were one of the more difficult tasks for me to get the hang of – especially iterating through conditions. Part of my struggle is that I made my loops too complicated…I tried addressing symptoms, not the overall desired behavior.

When I jumped into the Noughts and Crosses game, my algorithm was seven or eight steps long…I tried to account for each potential play as a ladder. Needless to say, I lost a lot of games. So, I simplified. I cut some steps. And lost again.

In college, a friend of mine was programming his own tic tac toe game as part of his CS master’s program. He explained the tree his program would use to make the best possible move. In it’s final state, it would always win or draw…never lose. To make it more interesting, he added a line to create a mistake at a random interval. It at least gave the human player a chance to win.

I came across an article explaining the Minimax algorithm. In short, it looks at a game state and finds the path which leads to a win or a draw. At the same time, it assumes that the other player wants to make us lose. It sounds confusing, and it certainly is, but the article linked did a great job explaining the principles. Ultimately, computers can be good at Tic Tac Toe because it can quickly build a move tree and execute the path to the best result.

Algorithms

I went back to Naughts and Crosses and took another stab. What was my desired goal? It wasn’t to win…I couldn’t win for two reasons: the game’s AI was probably using the minimax algorithm, and 2) I play second. It’s a significant disadvantage because I only get four board spaces while the opponent gets five. If I can’t win, I can try to force draw. I was able to make a simple program:

- Always make sure I don’t lose. Block the opponent’s three-in-a-row first.

- If they aren’t going to win, can I? Go for three in a row.

- If I don’t need to block, and I can’t win, just pick a free space.

Changing my approach was immensely helpful, because I didn’t have to worry about “what if?” moments. It finally clicked in my head – establish a general choice and iterate down the list to match your case. The algorithm I picked wasn’t perfect – I still lose about 30% of the time, but it’s much better than my earlier attempts.

Headaches

I like to tell myself that I enjoy thought problems. They get in my head and I have a hard time focusing on things. I’ve also learned (as explained above) that I need to keep it simple.

The Suitcases took me a while. Rather than writing it out, here’s a diagram of my solution:

I found the Pancake puzzle to be easier, probably because my daughter plays with stacking cups and blocks. I was able to get them ordered from largest to smallest in five flips.

The hard part of this task wasn’t finding a solution…it was to find a solution in the most efficient way possible. It’s easy to come up with an answer or a method, but that doesn’t mean it’s the best way to accomplish the task. To be totally honest, I wish the prompts hadn’t given as much information as they did. Once I knew what path to head down, I felt like I was stuck in one mindset. With students, we always face the danger of leading with too much information and boxing in their methods. Problem solving needs to have an ebb and flow of success and failure. The challenge is supporting students through the process of failure rather than labeling their work as a failure. There’s a major mindset difference, and it links back to Computational Thinking as the process of problem solving.

Each year teaching chemistry, I made it a point to my students that everything they learn over the course of the year is based on observation and best guesses. Up until 2009, we hadn’t actually seen a molecule or an atom…they’re just too small. What we can see is how they behave and change when stressed by an environmental factor (temperature, pressure, etc). By observing how substances change and looking for patterns, we can make pretty good guesses about the physical properties of very small pieces of matter.

A staple of any chemistry class is modeling molecular structures with the old wooden ball-and-stick model sets. Students look at molecular formulae and converting them into a structural formula on paper and a physical model. One year, I had a class turn it into a race to see which team could assemble the series of structures the fastest. The level of abstraction was high as students learned about bond formation, stability, and proper orientation of atoms. There was also a good deal of debugging with each submission because something was wrong, but I didn’t say what was wrong.

I enjoyed the rapid-pace building of models…students had fun and it broke up the monotony of class in the middle of the semester. The problem was that students didn’t internalize the ideas. The rapid prototyping was without structure and haphazard rather than thoughtful and methodical. I decided to shift the idea to the lab.

Limit the input in order to maximize the output.

I wish I’d run all of my labs this way.

Students had a simple task: find the mass of copper you produce. There were no handouts, there were no demonstrations. I wanted to see how groups would handle having very little information. What I saw was well thought out problem solving strategies. Each group walked through the problem step by step, coming up with solutions at each roadblock. Our class was only an hour long, so they had to work quickly to find a usable procedure. I was thrilled to see students trying their ideas in small scale before rushing to a larger, quantifiable sample. Filtration methods were tested. Heating was explored (to speed up the reaction). When they found something that worked, they started from the beginning, following their outlined procedure.

Groups who heated their reaction compared data with groups who didn’t. We then took those differences, plotted them on a graph, and talked about kinetics. There were graphs shown and best-fit lines plotted. I couldn’t have segued it better had I planned it out from the start.

My students and I had stumbled on computational thinking strategies before we knew what they were. Science is a process, and the problem solving techniques practiced in the lab are the same techniques used in programming, art, music, investigative reporting, storytelling…the list goes on. Grover & Pea (2013) talk about providing working in a “low floor, high ceiling” environment in order to promote problem solving. Students approached the problem easily and were able to reach much higher areas of thought as their solutions panned out.

Students need opportunities to problem solve in order to learn how to solve problems. By limiting the information available as well as leaving room for experimentation, my classes had a chance to look at a task from many different perspectives.

Game Theory

Games and learning go hand in hand. Children learn social interaction, communication, and even motor skills through playing. Remember, Piaget and early learning theorists broke learning down into formal and informal actions. Play is very much in the informal category, with school in the formal setting. Lately, the gamification movement has pushed to make formal instruction more like a game; emulating game mechanics in learning can have positive effects on overall understanding, engagement with, and recall of information.

I have to admit, I’ve been apprehensive of gamification due to poor implementation and a shallow approach focused on rote instruction disguised as games. Chris Hesselbein of IGNITEducation pointed me to an article by Joey Lee and Jessica Hammer (2011) in which they define “gamification” as “the use of game mechanics, dynamics, and frameworks to promote desired behaviors.” Thin slices – like badging – have made their way from business (FourSquare, etc) into the classroom (ClassBadges, Class Dojo). Specifically, Lee and Hammer note that gamers “recognize the value in extended practice,” develop persistence, and hone problem-solving techniques. However, they argue that “intuition” has brought basic game mechanics into schools, but a deeper look is necessary.

By harnessing the innate power of games, you can certainly begin to introduce the concepts of CT in a safe, supportive environment. In particular, Cognitive games ask players to “explore through active experimentation and discovery,” (Lee & Hammer 2011). In essence, experiment until you get it right. This approach – as in LightBot – is very effective for pushing students through the computational steps.

Gaming and Computational Thinking

I’m not going to dive deep into each of the ideas within Computational Thinking, but rather look at the game LightBot and how it relates to each component.

Symbols and Abstraction – All games involve abstraction. in LightBot, you give commands through simple glyphs. Your mind has to consider each command and visualize what the robot will do before making decisions. Barr & Stephensen (2011) note that “students are not tool users, but tool builders,” and LightBot gives students the tools necessary to build a working solution from nothing.

Decomposition – When I played the game through, I found that breaking each board down into straight runs helped me find a working solution. Corners were where I made mistakes, so working up to each corner helped me solve chunks in order to find a solution for the whole. Grover & Pea (2013) point out that a core idea of CT is “thinking like a computer scientist” to solve a problem. Thinking through dependencies before you can move in another direction is an invaluable skill in coding and something that computer scientists (or even hobbyists) learn very quickly to solve problems.

Efficiency – Segueing in from decomposition, efficient code is the goal. Physical limitations – like storage space or RAM – are present, but there is a sense of pride when you not only solve a problem, but when you solve it well. I read StackOverflow regularly for coding help, and it never ceases to amaze me at how tenacious some discussions get when users are debating the most elegant way to solve a problem. This also hints back to two main questions: “What can humans do better than computers? What can computers do better than humans?” (Wing 2006). By thinking through efficient and elegant solutions, my program will be that much better at doing its job.

Debugging – Depending on your personality, this is every programmer’s favorite or most loathed word. Debugging can be as complex as a restructure of code or as simple as finding a missing semicolon. Iteration and close reading are key in this process. It also requires that we think through what the program should be doing and test it against what it is doing to find clues. In fact, debugging alone combines all other aspects of CT as a capstone to any project. Grover & Pea (2013) note that there has been some research exploration into the idea of debugging as assessment because of the myriad cognitive tasks taking place parallel to one another.

Resources

Barr, V., & Stephenson, C. (2011). Bringing Computational Thinking to K-12: What is Involved and What is the Role of the Computer Science Education Community? ACM Inroads, 2(1), 48-54.

Grover, S., & Pea, R. (2013). Computational Thinking in K–12 A Review of the State of the Field. Educational Researcher, 42(1), 38-43.

Lee, J. J. & Hammer, J. (2011). Gamification in Education: What, How, Why Bother? Academic Exchange Quarterly, 15(2).

Wing, J. (2006). Computational thinking. Communications of the ACM, 49(3), 33-35.

This time last year, I was writing about increasing my household population by 50%. In the blink of an eye, a year has already gone by, and we went from an empty crib to a girl sitting in her own lawn chair.

I know it’s a cliché, but I feel like I blinked.

Excuse me while I blink again.

Trying to represent a familiar object in abstract ways is harder than you’d think. The goal of this particular assignment was to take three photos of an everyday “thing” and see if someone could figure out what it is. [STRIKEOUT:Rather than just posting a gallery, I wanted to have some more fun. As you scroll to each box (go slowly!) a picture will be revealed one at a time.] Can you guess the object in one? Two? Or will you need all three?

How many clues did it take you?

This is a follow up to my first post on Computational Thinking. For a background, go check it out before reading further.

I’m often victim to my own ignorance, and I think to be good thinkers, we need to fall prey to preconceived notions and half-formed thoughts. They give a lens through which we can analyze and consider areas of growth. To me, Computational Thinking (CT) was simply working in ones and zeros. Papert’s exploration of CT in Mindstorms has helped me connect philosophical ideas with actions which can be applied in the classroom.

Admittedly, my education psychology is a bit rusty. Of course, Piaget and the usual suspects (Skinner, Bloom, Gardner, Maslow, etc.) are familiar names, but the nuances of their ideas have faded. In particular, Piaget’s theory of learning as a formal process and the challenge that arises when we look at patterns of learning in children fascinated me. Papert makes a compelling connection between CT (programming, in particular) with learning a language.

Children learn based on the metaphors and cultural symbols surrounding them, which is why language is one of the first things to emerge. They are surrounded by speech and text. Words represent objects and become more abstract as they begin to understand the complexities and interactions between those symbols. “Learning languages is one of the things children do best,” (Papert, 1993, p. 6), and initially, without formal instruction. Applying the same ideas to math (which is the basis of the metaphor), children should be able to learn those abstract ideas at a very young age. Computers allow for that immersion to take place.

As for programming, Papert notes that building a computer function is analogous to things we do every day without thinking twice. The process we use to sort objects is the same thing a computer does as it runs through a loop. If that relationship can be experienced by students, they will begin to see programming as not a skill, but a culture, and something which will feed into all areas of their lives.

Computational Thinking should also inform instruction and feedback as well as fundamentally change the way students “think about thinking and learn about learning” (Papert, 1993, p. 23). In some ways, our educational system has taught students a rudimentary version of programming: it’s “right” or “wrong.” When computational thinking is introduced, the right/wrong dichotomy is replaced with “can it be fixed?” Learning is a process, and not one that the current educational system teaches very well. When students can learn through metacognition and reflection, we don’t have to wait for systemic change to enact reforms.

Finally, Papert recognizes that thinking “like a machine” is dangerous and should be avoided. While the concern is legitimate, it is often reductionist and misses the points of different methods of thinking. Papert says:

There are situations where [a step-by-step, literal mechanical fashion] is appropriate and useful…By deliberately learning to imitate mechanical thinking, the learner becomes able to articulate what mechanical thinking is and what it is not. The exercise can lead to greater confidence about the ability to choose a cognitive style that suits the problem (1993, p. 27).

In other words, we need to be teaching students different ways to analyze thinking, and one way to do that is through immersion with computers and problem solving in their language. Learning is multi-modal, and given the availability of computing devices and ease-of-entry for learning these languages, the implications for today’s educational system – 21 years later – are monumental and ripe for implementation.

Resources

Papert, S. (1993). Mindstorms: Children, computers, and powerful ideas. New York, NY: Basic Books, Inc.

Those who can read binary and those who can’t.

Te first activity we ran through for my Computational Thinking course was learning how to translate simple text into binary. Working at a software company, I feel like I’ve got a good handle on bits and bytes, pixels and codecs. I know that binary is the base of each of those, but I didn’t know how they stacked up with one another as the dataset. As I worked through encoding my name, seeing perfect squares helped me get the hang of the pattern pretty quickly. I also understand now why a kilobyte is 1024 bytes and not 1000. I had fun trying to do each letter without using a cheat sheet.

The picture is pretty tall, so click for full resolution.

I’m a scientist. I think in terms of what I can see and manipulate. Part of my training included a large amount of time making changes in systems, observing results, and making new changes in order to answer a question. It was systematic, measured, and thorough. Naturally, that tendency bleeds over into my relationships, parenting, hobbies, and pedagogy.

I’ve learned that much of the thinking we do from day to day is to solve problems.

I began learning HTML, CSS, and JavaScript a few years back, which shifted the way I think. I had to approach problems as patterns, analyzing cause-and-effect in real time through trial-and-error. The whole process is strikingly similar to scientific thought processes. I slowly realized that, at the core, programming is comparing true against false; one against zero.

Computational thinking is the process of breaking down problems into true and false statements one step at a time. Each results takes you down a path sequentially. Eventually, you reach the destination you were aiming for through this series of switches.

Teaching [STRIKEOUT:science] is as much about content as it is about thinking. Without thinking, students become repositories for facts with no faculties for problem solving. Thinking as a scientist, it is my responsibility to help students develop the patience and tenacity required to solve new problems to the new world we live in. Content is everywhere; I can look up information as I need it, and the same is true for our students. Finding the context for the content is more important, and exploring relationships with computational thinking processes can help.

I’ve explored the idea of using instructional methods to improve the quality of questions students ask, which would lead directly into idea analysis. Curiosity is natural, but not in the classroom…especially a high school science classroom. Our current expectations for education focus on the right answer, not on the right questions. Because of this, students have been inadvertently trained to disregard the unknown in favor of memorization. Focusing on questions as the basis for learning rather than facts will push our students to be thinkers, not reciters.

In case you missed it, there were two big stories in the past two weeks about schools selling or destroying their student devices. The Atlantic posted “Why Some Schools Are Selling Their iPads” and took a deep-dive into which device is the “best for interactive learning.” Additionally, Hoboken, NJ, made headlines when they publicly claimed “giving students laptops is a terrible idea.”

What it comes down to is that both schools – and schools across the country – look to devices to change the way teaching and learning happen.

Folly.

Since Apple released the iPad four years ago, starry-eyed educators have lauded the revolution that was to come. We saw the revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy and introduction of the 4 C’s of 21st Century Learning. Suddenly, every school had devices earmarked as a method for changing instruction. Every large computer manufacturer is now in education with devices, vying for attention from schools desperately trying to keep up (often at the expense of other programs but that’s a different discussion).

Rather than asking, “Does this device allow students to easily type?” educators really need to focus on new criterion:

- Can the device help students connect with the world? – Think of this as the “fourth wall” of education. Students need opportunities to connect with (both consume and produce) information outside of the building.

- Does the device dilute or enhance accessibility? – Often, devices are purchased with accessibility cited as a reason. But, neither teachers nor students receive training on how to enable that functionality.

- How will we change classroom practice? – Staff typically receives training in how to use the device, but rarely are they offered training on new methods or approaches to teaching and learning. Without support for changing practice, the computers can destroy a culture of learning.

I know I shouldn’t read the comments, but I did for both of these. 400+ comments combined, and most of them are disparaging at best. There is a general lack of understanding about why devices are important to the learning process and this is something schools in general are failing to communicate well. Perhaps this is also because of the inappropriate preparation happening when devices are purchased.

So, what can schools do?

- Research. – This is not a device pilot. If we’re focusing on larger issues of classroom practice and school culture, then the device doesn’t matter. This means reading research literature on education practice, site visits to neighboring schools, and speaking with experts on education theory. Having a solid pedagogical background will help solidify meaningful change.

- Build a core group of educators dedicated to cultural change. – These are the leaders who will slowly begin to help the school shift from one of didactic instruction to dynamic learning.

- Advocate for students. – Any change needs to keep students in mind, especially when it comes to large purchases. If the school cannot point to solid reasons (pedagogical and cultural) for why they are spending the money, they need to slow down and evaluate their motivations.

It’s disheartening to see coverage focus on purchases and failed plans rather than success stories and true change. Hopefully, as we continue to mature, we can shift the story.

Do a quick Google search for “disrupt education.” It seems 2013 in particular was a boom for companies looking to disrupt the current education system: MOOCs, apps, product launches, startups…pick your poison.

Disrupting the education space is the wrong way to influence change.

Disrupting has longevity issues. To be noticed in the startup realm, you need to make a big splash. Lots of big talk, lots of buzzwords, and lots of pie-in-the-sky ideas. All of which is geared to help that company get acquired by a larger entity (ahem Google ahem) with solid footing in education. These companies come and go, with lots and lots of money flowing through the door by venture capital. Don’t get burned by jumping on board too early.

Disruption minimizes impact. Because these companies are flying by the seat of their pants, there is very little research into the efficacy of their product on student learning. They all claim to raise scores, increase engagement, and do all the things you’re trying to do, all in one package. Yay! But, when it comes down to it, it’s a fun app for a few days, then it peters out. Students lose interest, teachers drop it. Many of these companies do not work with teachers (more are beginning to, which is nice) to see if the idea even floats in a classroom.

Disruption is niche focused. Our tools are becoming fragmented. You have your assessment app, the review game, the gradebook, and then the one giving you confidence levels…each of these companies focuses on a tiny niche slice of the everyday experience. Education is an artful science. We have to take the big picture into consideration when doing anything with students. As each new single-function app is released, we lose a piece of that picture and at the same time make our job much more complicated.

We need to transform education, not disrupt it.

Transformation is inherently different in scope and mindset than disruption.

Transformation is sustainable. Transformation is built around sustainability. We need to critically look at what education is now and how we can change it moving forward, planning for the future. There are things that need to come and go, but those decisions need to be informed by practice, data, and the impact on student learning.

Transformation is constructive. There are already seeds of change in schools. Administrators, in particular, are preparing for major change by laying a foundation of support for the teachers before student ever catch wind of the shift to come. Transformation is rooted in a community coming together and making a conscious decision to head in a new direction. These schools are building on their strengths and growing together.

Transformation has a wide scope. When you want to change an organization, you have to consider every component. How will it affect staff, students, parents, aides, administrators…without considering every stakeholder, you’re bound for trouble. That means the process is transparent and considers multiple avenues for problem solving. We’re undergoing a holistic shift, not treating symptomatic issues one at a time.

Clarification – I am not advocating that a single entity – company or school – can transform education on their own. True change takes collaborative action with flexibility and cooperation by many different groups.

Before starting this post, please go back and look at Part 1 to get the research justification for the outline below.

In an effort to make research more accessible and visible in the implementation of new ideas, here is a practical, “how-to” explanation of ways to get students to ask better questions.

While all of this can be done with paper and pencil in class, expanding the process to the web brings benefits. Students (and the teacher) can interact when and where they want. If you’re using an open community, you can also get feedback from outside sources. There is also a running record of the interactions asked and answered by each member of the community, which can be used for analysis, assessment, or just judging the health of the community.

Dan Meyer advocates questioning habits through making it a habit to ask. His keynote at CUE gives an example of how he practices asking good questions. (Please watch just a minute or two of the video. It is well worth the time.) This brings us to thing-to-try-number-one:

Have your students keep a list of questions. Not just content questions. Just questions.

Think of this as brain training. There is evidence showing that students who undergo training in asking questions score higher on information-based assessments than groups who do not receive training (Weiner 1978). Now, before you accuse me of reaching too far, the study also notes that they did not study the efficacy of a particular type of training. So, if we take Dan’s example and begin tracking perplexity, we are training our brains to pay attention to our surroundings, which could translate to the classroom. (As a closing side note, Dan also runs a website called 101 Questions which is a fun way to get kids thinking. You can also use it to upload content to get some feedback before using it with students.)

Thinking back to part 1, I gave a brief outline of a method called the “question formulation strategy. So, thing-to-try-number-two:

Try using the QFS rather than a more common tool like the KWL.

I know both strategies essentially do the same thing – get students to reflect on their learning as it happens. I like QFS better because the metacognitive processes the students engage in are open ended and content agnostic. The students are free to ask questions on anything they want, which gives then an open route to make connections on their own. The KWL also has a “finality” to it…once the student learns what they want to know (the “W” column), there is little invitation to continue exploring. QFS, on the other hand, encourages further questioning at every stage.

Finally, thing-to-try-number-three:

Use an online Q&A platform for peer feedback on questions.

Remember, there is evidence showing that questions alone aren’t enough. We need feedback. I mentiond earlier that StackExchange is a great platform for both asking and answering questions, but the added layer of voting and commenting serves as the quality control. Unfortunately, getting the platform for student use is more complicated.

StackExchange is a private company – the platform is not open source. I did some searching and there are some open-source alternatives which can be used, but they’re not insignificant to get set up.

The way I see it, there is a large community of educators with the know-how and the interest in getting something like I’ve described set up. I’m even willing to throw in my small-beans experience in helping to set up and maintain a site. If there is interest in experimenting with this idea (I’m not in the classroom, or I’d try it myself), leave a comment and we’ll see what we can do.

References

Weiner, C. J. (1978). The Effect of Training in Questioning and Student Question Generation on Reading Achievement.

I’ve been thinking over an idea since I saw this tweet from David Wees which linked a very well-written article defending the Common Core standards.

I found myself a little jealous that a group of math teachers was using StackExchange as a forum for education discussion. If you’re not familiar with the platform, it is a question/answer forum that relies on two things: credibility and crowdsourcing. Anyone may ask a question and as you engage with the community, you are granted more and more privileges. For instance, to leave a comment on a question, you have to earn x number of points. Answering questions, accepting answers, up- or down-voting questions and answers – each action comes from having a good reputation within the community.

This helps the community both ask good questions (interesting questions will be up-voted and have higher visibility) and provide reliable feedback (you can’t troll on the site because you need points to interact).

What does this have to do with education?

The Research

Observations in research literature show that teachers are usually the ones asking the questions, students are responding. Additionally, when students ask, the questions are “informative” or “unsophisticated” (Harper, Etkina, & Lin 2003; Hofstein, Navon, Kipnis, Mamlok-Naaman 2005). This can be boiled down to the fact that students “are schooled to become masters of answering questions and to remain novices at asking them” (Dillon 1990).

I think part of the struggle in helping students become better askers of questions is that we, as teachers, are rarely trained in methods which can be used to help develop those skills.

Dori & Herscovitz (1999) decided to improve questioning with an inquiry-based approach. The students were given a problem to solve (cleaner air) by asking questions to guide their learning. The research used the jigsaw method so no single group was faced with an overwhelming number of items to handle. At the end of the experiment, they saw a significant increase in the number of high-level questions asked by students. Interestingly, there was no difference in the number of low-level questions asked by either group.

This illustrated that the inquiry group did not move entirely away from low-level, informative questions, but rather added higher-level questions in their exploration. The students were also not asked to identify why certain questions were high-level and others were not. Metacognition is important to the learning process, so there needs to be an additional layer of intervention.

Koch & Eckstein (1991) performed a study which analyzed physics students’ ability to comprehend written text using questioning as a basis for learning. They note that the typical question/answer format – in which students are given questions during or after reading the text – is “suitable only if there is a teacher or other guide available to formulate the questions.” To “prepare students to assume a more active role in the learning process,” Koch & Eckstein developed the “question formulation strategy.”

This is broken into two parts: answer/questioning (A/Q) and peer feedback (PF).

Answer/Questioning

Developed specifically for teaching questioning skills, students summarize text, and the summary consists of questions, not facts like they’ve done for years and years. The students create three columns:

- Column 1 – Questions with answers in the text and the student believes they understand. The student also answers these questions on another piece of paper (or whatever medium you’re using).

- Column 2 – Questions with answers in the text but the student does not understand the idea.

- Column 3 – Questions related to the text, but are not discussed in the text itself.

Do you see what’s happening? There are three processes:

- Identifying what they understand and what they don’t (metacomprehension).

- Identifying content explicitly stated in text.

- Identifying causes for their lack of understanding (metacognitive). From the authors, “…was the answer never stated in the text and not understood, or was the answer not given in the text at all?”

Peer Feedback

Questions can be asked at length, and students can use the A/Q method explained above to improve their questioning habits, but there is little external quality control to the process. Traditionally, the teacher was responsible for giving quality feedback, but peer feedback can be just as helpful, which mitigates the workload and helps students expand on ideas more rapidly.

In short, students would read their questions out loud to the group and receive feedback on the spot. This process not only “helped students clarify fuzzy questions,” (1991) but it also increased comprehension through discussion.

The Implications

The study showed that students who used the A/Q format through the course had statistically significant higher performance on assessments than the control group. There was a second experimental group which layered PF on top of A/Q, and they had statistically significant gains over both of the other groups. These methods, when used in conjunction, help students not only ask better questions, but take and give qualitative feedback on the questions they are asking of the teacher and their peers.

I think StackExchange can work as a peer feedback for questions identified in the A/Q process.

Discussion in class is a powerful process. But questions come up when the class is not meeting. With question and answer forums like StackExchange, students can push the peer feedback portion of the process into an asynchronous environment. They are able to maintain the open forum and also – as a group – decide on the most important questions based on the voting process outlined earlier.

There is definitely an argument for this advocating a use of technology for the sake of using it, and I would agree in some cases. But, with the expansion of access points for students, using an online platform to help not only ask questions, but also develop the quality of the questions they’re asking, it becomes a much more compelling use of technology expanding the classroom opportunities rather than substitution only.

Resources

Dillon, J. T. (1990). The practice of questioning. London: Routledge.

Dori, Y. J., & Herscovitz, O. (1999). Question‐posing capability as an alternative evaluation method: Analysis of an environmental case study. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 36(4), 411-430.

Harper, K. A., Etkina, E., & Lin, Y. (2003). Encouraging and analyzing student questions in a large physics course: Meaningful patterns for instructors. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 40(8), 776-791.

Hofstein, A., Navon, O., Kipnis, M., & Mamlok‐Naaman, R. (2005). Developing students’ ability to ask more and better questions resulting from inquiry‐type chemistry laboratories. Journal of research in science teaching, 42(7), 791-806.

Koch, A. (2001). Training in metacognition and comprehension of physics texts. Science Education, 85(6), 758-768.

I read an article recently on the need for an “Instagram of Sound” – the idea being that I can record a short audio clip and then immediately share it to a network. After searching and searching, I couldn't find the one I read, but there's a good article on Motherboard which makes the case.

In the absence of such an app, I decided to try it with Instagram itself. I came up with a couple of rules:

- The video had to be still (or as little movement as possible)

- I couldn't appear in the video

- The video had to be shot straight up – as if my phone was just watching from the table

I think it's really interesting to think about how sound can communicate space, action, or surroundings. Our phones are with us everywhere…in reality, this is their experience. What do we miss if all we focus on is the visual? In fact, by playing videos on mute by default, I think Instagram is eroding the experience that sound can bring. I'm wondering if pushing the opposite direction will teach me something.

You can see the few I've done, follow me on Instagram, or search #soundaroundme through the app (their silly API doesn't allow for web searches).

Update 8/20/2014 8:30 AM: I have deactivated the script for this Twitter bot. It was fun, and the process is below if you want to read more. But, the Twitter feed is now inactive.

I’ve been fascinated by the proliferation of non-spammy Twitter bots in the last year. Chatbots have been around for a long time (remember SmarterChild on AIM? Anyone?) and they’ve migrated to Twitter. One of the more famous (and in the end, decidedly disappointing) chatbots on Twitter was @horse_ebooks. It would tweet non sequiturs at various intervals and currently, even though the account is no longer active, it has 203,000 followers. Twitter isn’t just for things with fingers anymore.

creative commons licensed ( BY ) flickr photo shared by JD Hancock <http://flickr.com/people/jdhancock>

creative commons licensed ( BY ) flickr photo shared by JD Hancock <http://flickr.com/people/jdhancock>

I think bots are fun because we can make them close to sounding normal, yet slightly…off. A turn of phrase is correct, but it doesn’t sit right. It’s a look into what we could come up with ourselves, but weren’t quite clever enough to pull off. In fact, “chatterbots” have been around since the 1990’s and there is an annual competition each year for the Loebner Prize, which is based on the Turing Test for true artificial intelligence.

Twitter bots are subverting the way the larger population thinks about online communication and how computer scripts running at intervals can become not only really convincing, but incredibly entertaining parts of our daily experience.

- *I started by building a simple bot which would search for “Shakespeare” on Twitter using the

Twython library from GitHub. Essentially, it lets you plug into Twitters REST 1.1 API using a python script. You can check out @ShakeTheBard to see some of the early tweets. That wasn’t much fun, though, because it mostly pulled quotes from plays. So, I took it one step farther.

The Markov Chain is an algorithm which can be used to generate random sequences (in this case, sentences) based on probability. So, in essence, it looks for a group of words – two or three at a time – and then determines a likely follow-up based on the frequency of those words and the text following them in the sampel. From StackOverflow:

- Split a body of text into tokens (words, punctuation).

- Build a frequency table. This is a data structure where for every word in your body of text, you have an entry (key). This key is mapped to another data structure that is basically a list of all the words that follow this word (the key) along with its frequency.

- Generate the Markov Chain. To do this, you select a starting point (a key from your frequency table) and then you randomly select another state to go to (the next word). The next word you choose, is dependent on its frequency (so some words are more probable than others). After that, you use this new word as the key and start over.

Sounds confusing, because it is.

I have a text document with every sonnet Shakespeare wrote. All 154. So each time the program runs, it chooses a starting point at random and generates a unique line of poetry based on the frequency of that choice as it goes through the algorithm. Finally, it tweets that line.

- *A lot of people use their own Twitter archive to make bots of

alternate-reality selves, but I haven’t gotten that deep into using the Twython library and pairing it with the Markov Chain library I found. So, for now, Bill is tweeting sonnet mashups. Some are pretty good, others not so much. But that’s the fun.

One of my favorites from testing (unfortunately, not tweeted) was:

Upon thyself thy thought, that thou shouldst depart.

In other words, “I thought to myself: ‘I’d better scram.’” Shakespeare is rolling over in his grave right now.

I see this as a 21st century version of giving 100 monkeys typewriters and infinite time to reproduce Shakespeare’s work. But, I don’t have 100 monkeys, and typewriters are inefficient. I’ll stick with the Pi.

I’m not expecting a ton of followers, and I’m not even sure I’ll leave the account active for any significant period of time. There is a lot of optimization I could do in the code, but I’m just exploring at this point. I’m not planning on posting the script, but if you want to see it, leave a note in the comments and I’ll get a link up.

A dangerous trend in education is the advent of the Learning Management System (LMS). Jim Groom writes about the danger of siloing our data across the web rather than sharing it freely. In other words, if you work in Edmodo, it’s difficult to share that content outside of Edmodo. It’s stuck and you’re robbed of the ability to share your work with a larger group who can build on, improve, and re-share.

The LMS has taken off because it takes the difficulty out of piecing things together. Unfortunately, rather than taking the time to look at alternatives, we go for the easy answer without considering the implications of locking out content until it’s almost too late.

I’ve started a document which walks through how to connect documents, blogs, videos, and calendars all through RSS. Rather than locking your content away, RSS pulls from various sources – preferably ones you control – to deliver content directly to you or your students. RSS has been around for a long time, but it takes time to set up and manage, which is why most people pass over the option.

The goal of this document is to help you connect your dots. It’s growing and dynamic. I’ll update it, add, and take away. Feel free to copy it for yourself and share it with your colleagues. We need to begin talking about controlling our content and I think this is a great place to start.